The most popular Go dependency is…

…

As you know, destination is not as important as the journey, so now that we got this out of the way, bear with me for the rest of this article, and I’ll give you the top 10, and many more stats 😊 You might even learn a few things along the way!

Without usage statistics, finding useful and reliable dependencies can be a bit of a challenge. In the Go community, we basically have to rely either:

- on "brand" name reputation: there are some very well known packages (gin, cobra, testify…) and organizations (Google, gorilla…) that we can trust,

- or on side metrics such as number of GitHub stars, number of open issues, last activity, and more.

All of this can sometimes help get a feeling of how widely used and trusted a Go module is, but we could get more. What I personally want is knowing how many times a module is actually required as a project dependency to get a feeling of how "battle-tested" a library is. But to do this, I would need to build a graph of the whole (open source) ecosystem, which would be insane… You can see where this is going 😉

Mapping the Go ecosystem

My first idea was to build a list of repositories (a seed) to use as a starting point. The goal was to read the dependencies of these modules from their go.mod, download each of them, read the dependencies of these modules from their go.mod, download each of them, read the dependencies of these modules from their go.mod, download each of… well, you know the deal.

I implemented this idea on the v1 branch of my repository using mainly Github-Ranking and awesome-go as sources for building the seed. I ultimately abandoned the idea because of a few shortcomings:

- the sample is largely incomplete,

- cloning so many Git repositories to find their

go.modis reaaally painful and slow, - and it’s particularly biased towards repositories hosted on GitHub.

Luckily for me, I came up with a second idea: the Go modules ecosystem relies on a centralized public proxy, so surely they expose some information on these modules. And they in fact do so! The proxy APIs are documented on proxy.golang.org:

- proxy.golang.org exposes metadata on each module (versions, latest, mod file…),

- index.golang.org exposes a feed of all the published module versions since the introduction of the Go proxy (

2019-04-10T19:08:52.997264Z, if you want to make sure not to forget its birthday).

I used this information to locally download the whole index (module names and versions) since 2019. The downloaded data is available in goproxy-modules. This can be used as a local immutable cache.

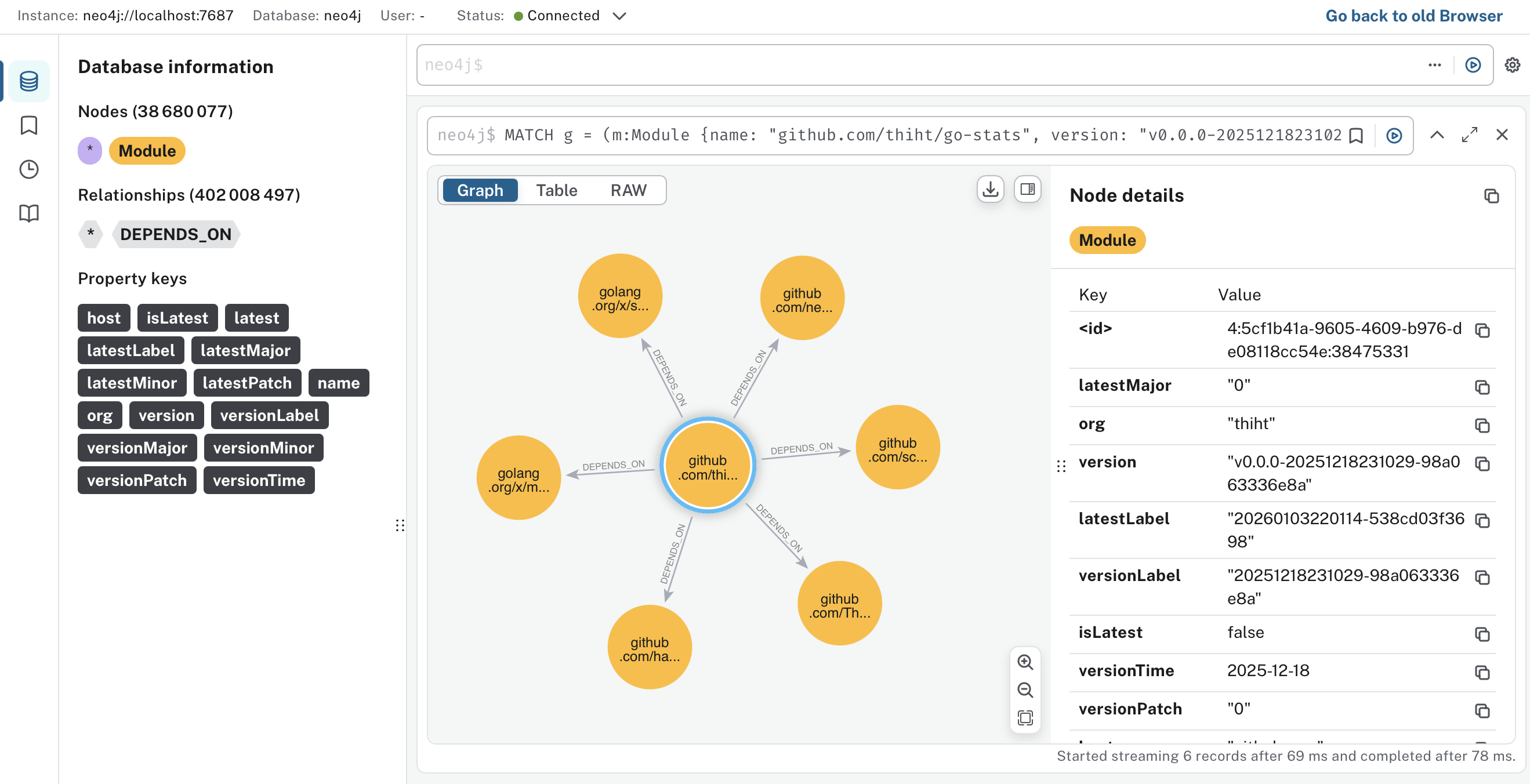

With all this data available locally, the seed is now pretty much exhaustive, and more suitable for data analysis. The processing now simply consists of iterating over every single module, downloading their go.mod file and listing their dependencies. The resulting graph can then trivially be inserted in a specialized graph database like Neo4j.

Deep diving

Neo4j is a graph oriented database. It means that unlike relational databases, it works on... graphs. The primary way to store data in Neo4j is using nodes and relationships. This specialized data structure makes it extremely simple to model, and more importantly query huge graphs.

Neo4j, like many NoSQL databases, is schemaless, meaning you don't need to define a schema before creating data. That doesn't mean we don't need a schema, so let's see what we need!

erDiagram

Module {

string name

string version

}

Module ||--o{ Module : DEPENDS_ON

A Go module is basically identified by its name (eg. github.com/stretchr/testify or go.yaml.in/yaml/v4) and its version. Each module can depend on other modules. We can add more properties to our nodes later on as needed.

Creating nodes

Neo4j uses Cypher as a query language. Inserting data with Cypher can be done with the CREATE clause, but in go-stats I've decided to use the MERGE clause instead because it behaves as an upsert, letting you update or do nothing in case a node already exists.

The basic Cypher query to upsert a module node is:

MERGE (m:Module { name: $name, version: $version })

RETURN m:Module is a label attached to the node. You can think of it as the type of the node. name and version are properties of the node, they're the data belonging to each specific node.

To make sure we can't create multiple nodes with the same name-version pair, a unicity constraint is needed:

CREATE CONSTRAINT module_identity IF NOT EXISTS

FOR (m:Module)

REQUIRE (m.name, m.version) IS UNIQUEThanks to this constraint, if MERGE is called a second time with the same name and version properties, it won't do anything.

Creating relationships

We can then create the dependency relationships between our module nodes:

MATCH (dependency:Module { name: $dependencyName, version: $dependencyVersion })

MATCH (dependent:Module { name: $dependentName, version: $dependentVersion })

MERGE (dependent)-[:DEPENDS_ON]->(dependency)

RETURN dependency, dependentThis query will:

- find modules that were created earlier using the

MATCHclause and assign them todependencyanddependent, - create the directed relationship between them using the

-[:DEPENDS_ON]->syntax.

The Go index is naturally sorted chronologically. So as long as we iterate over it sequentially, it means that if a module (dependent) depends on another module (dependency), then dependency was necessarily added to the graph before dependent. If this condition doesn't hold for some reason (if we were to decide to parallelize the insertions for example), we could simply rewrite the query as:

MERGE (dependency:Module { name: $dependencyName, version: $dependencyVersion })

MERGE (dependent:Module { name: $dependentName, version: $dependentVersion })

MERGE (dependent)-[:DEPENDS_ON]->(dependency)

RETURN dependency, dependentUsing MERGE instead of MATCH would ensure the node gets created if it doesn't exist already.

These queries are simplified (but close!) variants of what I actually did in go-stats. The main difference is that I enriched the nodes with some additional properties:

- version timestamp,

- latest version,

- semantic version splitting (major, minor, patch, label),

- host, organisation, and more.

Digging into the graph

After running go-stats for a few days, I ended up with a graph of roughly 40 million nodes, and 400 million relationships… that's quite a lot! The first thing these numbers tell us is that Go modules have 10 direct dependencies on average.

For more interesting stats, let's write some Cypher, shall we?

Indexing

With this volume of data, the absolute first thing to do (that I clearly didn't do at first) is to create relevant indexes. I was initially under the impression that the module_identity constraint previously created would also act as an index for :Module.name since it's a composite unique index. I was wrong, and creating a specific index was necessary:

CREATE INDEX module_name_idx IF NOT EXISTS

FOR (m:Module) ON (m.name)I created other indexes as needed, and to do so the Cypher PROFILE was a tremendous help.

Find the direct dependents of a module

As a warm-up, and to learn a bit more about Cypher, let's list the dependents of a specific module:

MATCH (dependency:Module { name: 'github.com/pkg/errors', version: 'v0.9.1' })

MATCH (dependent:Module)-[:DEPENDS_ON]->(dependency)

WHERE dependent.isLatest

RETURN dependent.versionTime.year AS year, COUNT(dependent) AS nbDependentsI chose github.com/pkg/errors@v0.9.1 because it's a module that was deprecated long ago, I find it interesting to know how much it's still used in the wild. Let's break the query down line by line:

-

MATCH (dependency:Module { name: 'xxx', version: 'xxx' })-

finds the module node (we know it's unique because of the constraint we declared earlier) with the given

nameandversion. This is equivalent to:MATCH (dependency:Module) WHERE dependency.name = 'xxx' AND dependency.version = 'xxx'

-

-

MATCH (dependency)<-[:DEPENDS_ON]-(dependent:Module)- finds the module nodes with a direct

DEPENDS_ONrelationship towardsdependency.

- finds the module nodes with a direct

-

WHERE dependent.isLatest- keeps

dependentsmodules that are in their latest version. This is useful because for any modulexdepends ongithub.com/pkg/errors@v0.9.1, we don't want to count all the versions ofxthat depend on it. The latest is more relevant to us.

- keeps

-

RETURN dependent.versionTime.year AS year, COUNT(dependent) AS nbDependents-

simply counts the total dependents of

github.com/pkg/errors@v0.9.1and group by release year of the dependent. If we wanted to list them, we could write:RETURN dependent.name AS dependentName ORDER BY dependentName;

-

Results:

| year | nbDependents |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 3 |

| 2020 | 6,774 |

| 2021 | 10,680 |

| 2022 | 11,747 |

| 2023 | 8,992 |

| 2024 | 12,220 |

| 2025 | 16,001 |

That's a lot of dependents for a dead library!

Find the transitive dependents of a module

Neo4j really shines at graph traversal. Navigating relationships transitively requires virtually no changes:

MATCH (dependency:Module { name: 'github.com/pkg/errors', version: 'v0.9.1' })

MATCH (dependent:Module)-[:DEPENDS_ON*1..]->(dependency)

WHERE dependent.isLatest

RETURN COUNT(dependent) AS nbDependentsThe only difference with the previous query is *1.., asking Neo4j to follow the DEPENDS_ON relationship transitively. We could also limit it to 2 levels with *1..2.

I find this interesting, because in the case of the query for direct dependencies, if we used a relational database, the SQL query would be pretty simple:

SELECT COUNT(*) AS nb_dependents

FROM dependencies d

JOIN modules m ON m.id = d.dependent_id

JOIN modules dependency ON dependency.id = d.dependency_id

WHERE dependency.name = 'github.com/pkg/errors'

AND dependency.version = 'v0.9.1'

AND m.is_latest = true;but what's as simple as *1.. in Cypher would make a dramatically more complex SQL query:

-- Example using a recursive CTE, I'm not sure every SGBDR implements it in the same way

WITH RECURSIVE dependents_cte AS (

SELECT m.id AS dependency_id

FROM modules m

WHERE m.name = 'github.com/pkg/errors'

AND m.version = 'v0.9.1'

UNION ALL

SELECT d.dependent_id

FROM dependencies d

JOIN dependents_cte cte ON d.dependency_id = cte.dependency_id

)

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT m.id) AS nb_dependents

FROM modules m

WHERE m.id IN (SELECT dependency_id FROM dependents_cte)

AND m.is_latest = true;Top 10 most used dependencies

Using the constructs from above, the query is once again pretty similar.

MATCH (dependent:Module)-[:DEPENDS_ON]->(dependency:Module)

WHERE dependent.isLatest

RETURN dependency.name AS dependencyName, COUNT(dependent) AS nbDependents

ORDER BY nbDependents DESC

LIMIT 10;Results:

| dependencyName | nbDependents |

|---|---|

| github.com/stretchr/testify | 259,237 |

| github.com/google/uuid | 104,877 |

| golang.org/x/crypto | 100,633 |

| google.golang.org/grpc | 97,228 |

| github.com/spf13/cobra | 93,062 |

| github.com/pkg/errors | 92,491 |

| golang.org/x/net | 76,722 |

| google.golang.org/protobuf | 74,971 |

| github.com/sirupsen/logrus | 71,730 |

| github.com/spf13/viper | 64,174 |

github.com/stretchr/testify is comfortably ahead of other dependencies as the most used in the open source Go ecosystem.

Unsurprisingly, github.com/google/uuid is also a staple library used pretty much everywhere.

The golang.org/x/ dependencies also hold a strong place as the extended stdlib, as well as the infamous github.com/pkg/errors.

To get more insights, you can download the top 100 as a CSV file.

If you want to run your own queries, feel free to download my Neo4j dump via BitTorrent:

To load it in a Neo4j instance, please follow these instructions:

- clone

go-stats, - copy the dump file to

neo4j/backups/neo4j.dump(the filename is important), - execute

task neo4j:backup:load, this will write the data toneo4j/data, - run

task neo4j:startto start Neo4j.

You can then open localhost:7474 (no credentials needed) to use the Neo4j browser.

That's all Folks!

I hope you had a good time reading this post, and that you learned a thing or two!

I'll probably continue playing around with this side-project as I have more ideas to explore. Specifically, I'd like to enrich the graph with more metadata, such as GitHub stars and tags. So stay tuned to the GitHub project if you want to follow the upcoming developments.